为了在世界上穿行,我们的大脑必须对周围的物理世界产生直观的理解,然后我们用它来解释进入大脑的感官信息

大脑是如何发展这种直觉理解的?许多科学家认为,它可能使用类似于“自我监督学习”的过程。这种类型的机器学习最初是为了创建更高效的计算机视觉模型而开发的,它允许计算模型仅根据视觉场景之间的相似性和差异来学习视觉场景,而不需要标签或其他信息

研究人员表示,这些发现表明,这些模型能够学习物理世界的表征,可以用来准确预测世界上会发生什么,哺乳动物的大脑可能也在使用同样的策略

ICoN中心的博士后Aran Nayebi说:“我们工作的主题是,旨在帮助制造更好机器人的人工智能最终也成为了更好地理解大脑的框架。”。“我们还不能说它是否是整个大脑,但在不同的尺度和不同的大脑区域,我们的结果似乎暗示了一个组织原则。”

Nayebi是其中一项研究的主要作者,该研究与前麻省理工学院博士后、现就职于元现实实验室的Rishi Rajalingham和资深作者Mehrdad Jazaeri合著,大脑和认知科学副教授,麦戈文大脑研究所成员;以及大脑和认知科学助理教授、麦戈文研究所副研究员Robert Yang

ICoN中心主任、大脑和认知科学教授、麦戈文研究所副成员Ila Fiete是另一项研究的资深作者,该研究由麻省理工学院研究生Mikail Khona和前麻省理工大学高级研究员Rylan Schaeffer共同领导

这两项研究都将在12月举行的2023年神经信息处理系统会议上发表。对物理世界建模

早期的计算机视觉模型主要依赖于监督学习。使用这种方法,模型被训练来对每个都标有名字的图像进行分类——猫、车等。由此产生的模型运行良好,但这种类型的训练需要大量的人类标记数据

为了创造一种更有效的替代方案,近年来,研究人员转向了通过一种称为对比自监督学习的技术建立的模型。这种类型的学习允许算法在不提供外部标签的情况下,根据对象彼此的相似程度来学习对对象进行分类

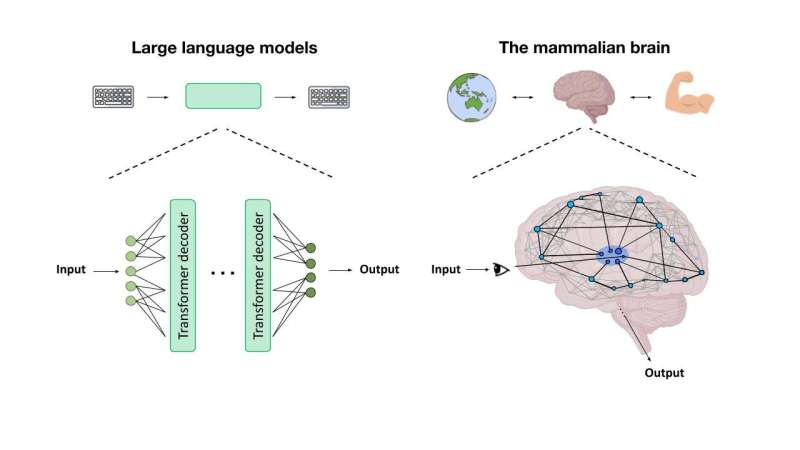

这些类型的模型,也称为神经网络,由数千或数百万个相互连接的处理单元组成。每个节点与网络中的其他节点具有不同强度的连接。当网络分析大量数据时,这些连接的强度会随着网络学习执行所需任务而变化

当模型执行特定任务时,可以测量网络中不同单元的活动模式。每个单位的活动都可以表示为一种放电模式,类似于大脑中神经元的放电模式。Nayebi和其他人之前的工作表明,自我监督的视觉模型产生的活动与哺乳动物大脑的视觉处理系统中看到的类似

在这两项新的NeurIPS研究中,研究人员开始探索其他认知功能的自我监督计算模型是否也可能显示出与哺乳动物大脑的相似性。在Nayebi领导的这项研究中,研究人员训练了自我监督的模型,通过数十万个描绘日常场景的自然主义视频来预测环境的未来状态

“在过去十年左右的时间里,在认知神经科学中,建立神经网络模型的主要方法是在单个认知任务中训练这些网络。但以这种方式训练的模型很少推广到其他任务中,”杨说。“在这里,我们测试了我们是否可以通过首先使用自我监督学习对自然数据进行训练,然后在实验室环境中进行评估,来建立认知的某些方面的模型。”

一旦训练了模型,研究人员就将其推广到他们称之为“心理乒乓球”的任务中。这类似于电子游戏“乒乓球”,玩家移动球拍击打在屏幕上移动的球。在Mental Pong版本中,球在击中球拍前不久就消失了,因此玩家必须估计其轨迹才能击球

研究人员发现

Once the model was trained, the researchers had it generalize to a task they call "Mental-Pong." This is similar to the video game Pong, where a player moves a paddle to hit a ball traveling across the screen. In the Mental-Pong version, the ball disappears shortly before hitting the paddle, so the player has to estimate its trajectory in order to hit the ball.

The researchers found that the model was able to track the hidden ball's trajectory with accuracy similar to that of neurons in the mammalian brain, which had been shown in a previous study by Rajalingham and Jazayeri to simulate its trajectory—a cognitive phenomenon known as "mental simulation." Furthermore, the neural activation patterns seen within the model were similar to those seen in the brains of animals as they played the game—specifically, in a part of the brain called the dorsomedial frontal cortex. No other class of computational model has been able to match the biological data as closely as this one, the researchers say.

"There are many efforts in the machine learning community to create artificial intelligence," Jazayeri says. "The relevance of these models to neurobiology hinges on their ability to additionally capture the inner workings of the brain. The fact that Aran's model predicts neural data is really important as it suggests that we may be getting closer to building artificial systems that emulate natural intelligence."

Navigating the world

The study led by Khona, Schaeffer, and Fiete focused on a type of specialized neurons known as grid cells. These cells, located in the entorhinal cortex, help animals to navigate, working together with place cells located in the hippocampus.

While place cells fire whenever an animal is in a specific location, grid cells fire only when the animal is at one of the vertices of a triangular lattice. Groups of grid cells create overlapping lattices of different sizes, which allows them to encode a large number of positions using a relatively small number of cells.

In recent studies, researchers have trained supervised neural networks to mimic grid cell function by predicting an animal's next location based on its starting point and velocity, a task known as path integration. However, these models hinged on access to privileged information about absolute space at all times—information that the animal does not have.

Inspired by the striking coding properties of the multiperiodic grid-cell code for space, the MIT team trained a contrastive self-supervised model to both perform this same path integration task and represent space efficiently while doing so. For the training data, they used sequences of velocity inputs. The model learned to distinguish positions based on whether they were similar or different—nearby positions generated similar codes, but further positions generated more different codes.

"It's similar to training models on images, where if two images are both heads of cats, their codes should be similar, but if one is the head of a cat and one is a truck, then you want their codes to repel," Khona says. "We're taking that same idea but applying it to spatial trajectories."

Once the model was trained, the researchers found that the activation patterns of the nodes within the model formed several lattice patterns with different periods, very similar to those formed by grid cells in the brain.

"What excites me about this work is that it makes connections between mathematical work on the striking information-theoretic properties of the grid cell code and the computation of path integration," Fiete says. "While the mathematical work was analytic—what properties does the grid cell code possess?—the approach of optimizing coding efficiency through self-supervised learning and obtaining grid-like tuning is synthetic: It shows what properties might be necessary and sufficient to explain why the brain has grid cells."